SWT: The Smash World Tour

The Smash World Tour 2021 is a global scale event featuring both Super Smash Bros. Ultimate and Super Smash Bros. Melee videogames. Players from around the world play in regional tournaments to classify to the finals in the USA. Because of the Covid situation, the regional events are held online to decide a small group of players that classify to the in-person regional finals.

The world was divided into the following regions:

- Mexico

- Oceania

- Central America - South

- South America

- Europe

- Japan

- East Asia

- North America - Southwest

- North America - Northwest

- North America - Southeast

- North America - Northeast

This division takes in consideration the already known strong regions, to guarantee more spots for players from those regions in the finals.

Tournament bracket seeding

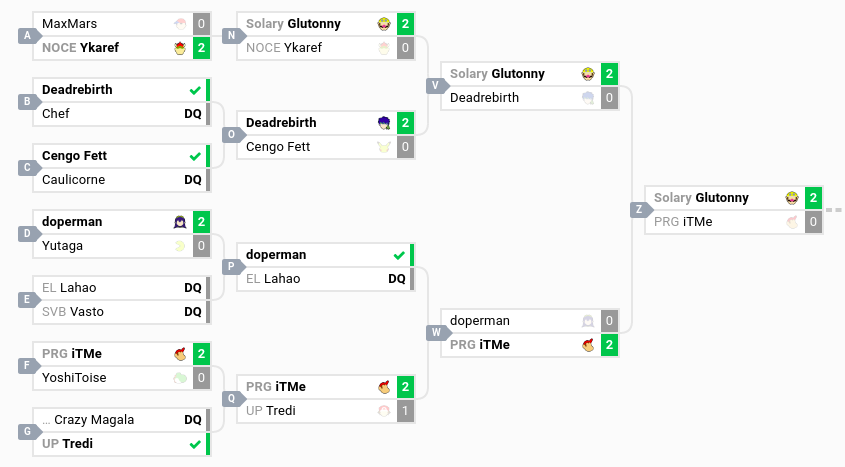

Part of a tournament bracket. Source: smash.gg.

When organizing a tournament bracket, we usually use the process known as seeding. Seeding is a way of generating a bracket where the tournament organizer projects the expected outcome of the tournament. The concept can seem weird at first, but it has multiple advantages for both players and viewers:

- Matches between the best players will happen only later in tournament;

- For each player seeded X, the match that is projected to eliminate them is versus the player seeded X-1. That means it’s the most balanced match possible, where this player could outperform their original seed;

- Results are generally more consistent;

A similar concept is applied in the FIFA World Cup, where a known strong team is assigned for each group or pool to make it so they only meet in later stages of the tournament. This also ensures that strong teams do not eliminate each other in the pools stage, which would lead to unbalanced matches later on.

Delay: a huge issue

Fighting game networking

Fighting games such as Super Smash Bros. Ultimate are extremely sensitive to internet delay. Fighting games are deterministic, which means that with the same configurations and the same inputs, the results are always the same. Because of this, it’s easy to implement Replay features by just saving the inputs in a match in order and then playing a new match with the same configuration to have the exact same result. The same could be said about networked matches: if you send and receive the players’ inputs in order, the match in both ends happens in the exact same way.

However, in the case of a networked match, the game can only run a frame if there’s input from both players available. The most common strategy used is creating a buffer system, where you pack input for a few frames for sending/receiving inputs for the game to run smoothly. If the communication delay between two players is small, it can work well. The problems come when the delay is too high. In this case, the two main problems that arise are:

- If the buffer is too low, or the network delay varies too much, the flow of the gameplay will constantly be interrupted by small stutters

- If the buffer is too high, the gameplay will be susceptible to a long delay between button presses and the on-screen outcome

The added delay is extremely frustrating for a competitor because it changes how the game strategies work. Strategies that require quick reactions become uneffective. Not to mention that every single frame added to the delay buffer is exponentially felt by both competitors, which ends up in a terrible experience for both players. Matches between players that are geographically far from each other become more unplayable the more they are distant from each other.

That being said, the experience of playing an online match can be very different from playing offline, and the outcome of matches can be affected by many more factors that can obfuscate the default skill factor.

Nowadays there are fighting game networking implementation strategies with extreme success in avoiding these issues (GGPO), however they’re still not popular among most developers, mostly because they require the game to be structured around them from the start.

See Explaining how fighting games use delay-based and rollback netcode for more details and neat visual explanations of input buffering and delay.

South America’s internet infrastructure

The following data is assumed by me in my tests and observations over the data I have available.

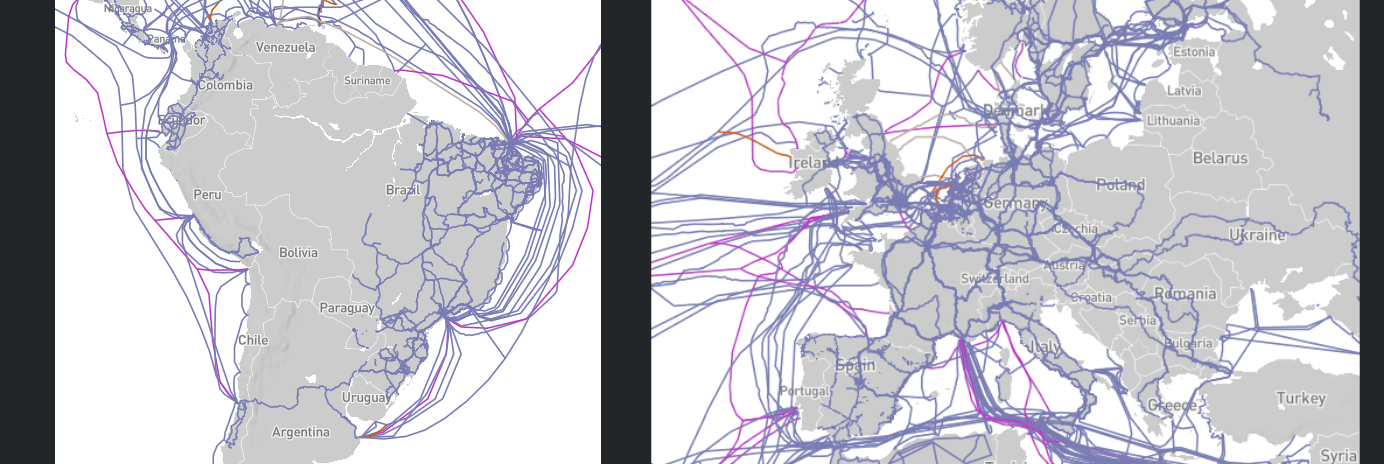

South America doesn’t have a great internet infrastructure. There are submarine cables that go along the east and west sides of the continent, and a cable below, between Valparaíso (Chile) and Las Toninas (Argentina), that connects both sides. In a way, the better internet route between countries seems to form a “U” that goes around the continent.

High-speed internet cable infrastructure, comparing South America and Europe. Source: Infrapedia.

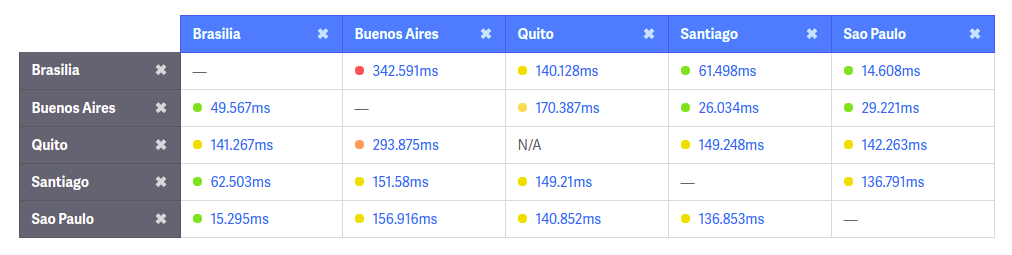

If you measure PING between different countries, you’ll notice that playing a match between some regions could be unviable due to high delay. The worst cases come from regions that are farther away from the ocean, because they have an added delay until they reach the oceanic cables.

If you play a match between Brasília and Quito, this should be the expected internet route. The added delay in “X”, that a lot of times could be using lower-speed cables, can make the PING skyrocket. These are usually the worst cases. Map image source: Infrapedia.

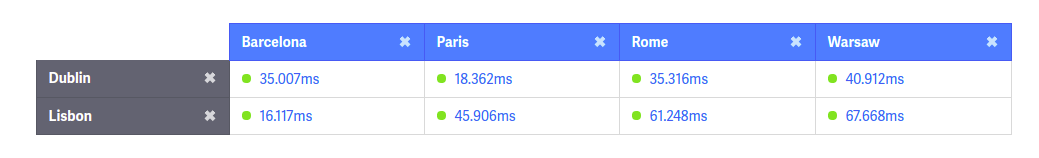

PING between different regions in South America, then Europe. Notice how PING from one extreme to another in Europe is still lower than most routes in South America. Source: WonderNetwork.

Seeding strategy

I was in charge of the South American SWT seeding. In my opinion, just doing a regular skill-based seeding wouldn’t work with our internet infrastructure. It would lead to bad matches and this could affect their outcome. Considering the top 16 players would classify to in-person regional finals, I decided to try something new: seeding the tournament based on skill and internet latency.

Algorithms!

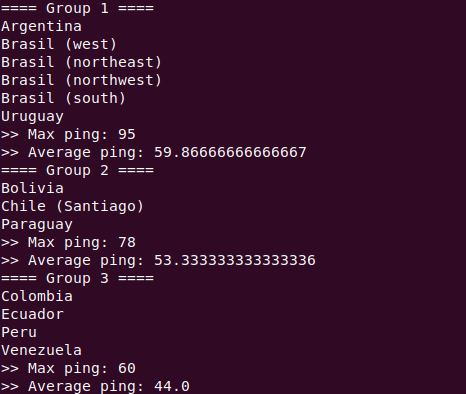

In order to generate the seeding based on internet latency, I first had to group countries by PING. My approach for this was gathering PING data between different regions from WonderNetwork and running a Agglomerative Clustering algorithm. As a result, I got a “optimal” division of South America into three groups.

“Optimal” PING groups output by the algorithm

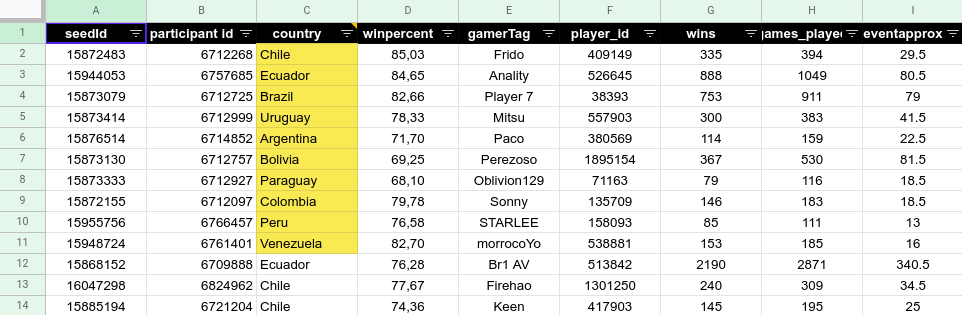

Following that, I created a regular, skill-based seeding. One small twist I made was to put each country’s #1 seeded player as the top seeds, just so they end up in different groups/pools in a way of trying to increase country representation in top 16. After that, a regular ordering follows.

Original Seeding

Original Seeding

The tournament bracket itself had 519 players, initially divided into 16 groups/pools. Based on the number of players from each PING group, the pools were assigned to the following PING groups, in order: 2 3 2 1 2 3 2 1 2 3 2 1 2 3 2 1. In doing so, we “guarantee” that we avoid bad matches in pools. Furthermore, because of this particular ordering that alternates groups 1 and 3 with group 2, the players that procceed to top 16 will play in matches between groups (1 vs 2) and (2 vs 3), which are the better matches between different groups, rather than (1 vs 3).

The original seeding was, then, put in an algorithmm I developed to sort the players between groups. Smash.gg expects to receive a regular seeding order in order for it to generate a bracket, so I had to understand how it worked. Turns out it places players in pools, in order (1 to 16), then goes back placing players 17 to 32 in reverse order in pools (16 to 1), and so on.

My algorithm went through the original seeding with 3 different cursors (one for each type of PING group), placing the players in the pools they should fit, based on their country of origin. This led to an overall reordering of “global” seedings, but one that wouldn’t affect the tournament that much: top players are still on the top, and will be projected to only meet each other later in bracket.

One particular case that made me very anxious about this reordering was Br1 AV: originally seeded 11, he was reordered to 19. If you look at the general seeding without considering this unconventional seeding strategy, it would seem like this player was seeded too low. In the end, his bracket projection worked as expected and he was one of the two players in Grand Finals.

Another possible problem is that, even if we avoid internet latency earlier in bracket, won’t it eventually happen later? And the answer is yes, it will. We had some issues (especially in the losers bracket where players are placed in the order they lose matches).

In the end, my argument is: even if top 16 has matches with a terrible experience for the players, at least they already classified to the in-person regional finals where they will be playing offline. Additionally, their bracket up to top 16 should have avoided internet latency, so the matches had the lowest influence from internet latency and input buffering that they could have.

Conclusion

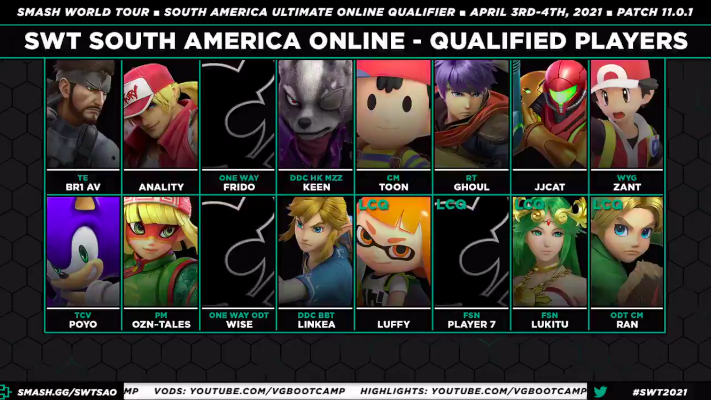

Classified Players that will play the in-person regional finals later on. Source: SmashWorldTour@Twitter

Classified Players that will play the in-person regional finals later on. Source: SmashWorldTour@Twitter

With all challenges we had to deal with, I think the overall result of our efforts contributed to a better experience for all players. I asked for and received good feedback from players in all levels of skill. The classified players are mostly the ones we expected, and there’s representation from multiple countries.

I cannot thank the community enough for believing in me, and in understanding my unorthodox seeding strategy. I’m also very thankful of how the community handled some latency-related issues that occurred in the tournament.

In a way I also developed a study that helps the community in understanding better South America’s network-related issues and needs.

If a second edition of the Smash World Tour ever happens, I really hope we won’t be in the middle of a pandemic and that all regional tournaments happen in-person.